Outline

Introduction – Importance of Mode of Action (MOA) to understanding effects on insects and humans

Active ingredients (AIs) in 1974 reflected screened for maximum toxicity, ignoring environmental persistence and secondary effects; Current AIs and MOAs reflect screening for lower mammalian toxicity, fewer environmental efffects, illustrated with California data on pesticide use and illness surveillance from 2016

Historical use

Sulfur, arsenic, and nicotine going back centuries, but without precise timelines

Materials developed from natural products

cholinesterase inibitors, pyrethroids, rotenone

initial synthesis of DDT, lindane without recognition of insecticidal properties

19th century MOA based on type of application –

on contact w exterior of insect vs ingestion, arsenic compounds used extensively after 1870,

Late 19th century use

Commercial distribution of pyrethrins

Arsenic use to control Colorado potato beetle

Early 20th Century, WW II and post-war

Discovery of neurotransmitters, mechanisms of signaling and breakdown, mechanism of pyrethrin/pyrethroids, rotenone

Synthesis of multiple, synthetic ChE inhibitors, screening process based on animal tests, selecting most toxic compounds, adding more reactive substructures

Post-war use of arsenic, gradual replacement with DDT, ChE inhibitors, and pyrethrins (and synthetic derivatives)

Case examples for specific MOAs: ChE inhibitors, pyrethroids, and inhibitors of mitochondrial energy production (rotesnone and others).

Case example for compounds with multiple sites of action – Methyl bromide

Introduction

Following the outline above, this brief reviews changes in methods for studying pesticide MOAs and the development of AIs with novel MOAs. This starts by comparison California pesticide use reporting and illness surveillance in 1974 and current use and illness data.

Historical pesticide use vs current use

The 1974 use data (repreenting the beginning of use reporting in California) 123 Als 25,970,604.9 Kg (11,780,082.2 lbs) of reported use, 14 IRC groups and 3 non-lRC groups).

2016 California use data shows 251 active ingredients (Als), with 28,977,296.8 lbs (883,928.0 Kg) of reported use, distributed among 36 insect resistance classification (IRC) mode of action (MOA) groups, as well as 3 non-lRC groups – soaps & other dessicants, inhibitors of insect metabolism. and insect pheromones.

This change in use patterns coincided with a marked decrease in reported illnesses in agricultural workers.

1974 –1,157 occupational illnesses, principally agricultural exposures, workers’ compensation reporting: fumigants & ChE-inhibitor exposures; dermatitis in applicators and field workers – propargite vs sulfur

2016 –479 occupational illnesses in, 213 Ag exposures, 259 non-Ag, 7 unclassified, reported through CA Poison Control System in 2016. Very high % of non-ag cases from handling anti-microbials

Variations in chemical structures

Understanding the changes in illness and use patterns requires knowledge of the history of pesticide use and changes in the understanding of mode of action.

Spreadsheet with a timeline of pesticide use history prior to 1974.

The most dramatic changes become apparent in reviewing the variation in chemical structures associated with each MOA (see link to downloadable reference spreadsheet below). The changes appear less clear when using common chemical names, trade names or multi-syllabic names meant to provide described complex structural details.

Spreadsheet with chemical structures and biological targets for current and prior pesticide active ingredients

https://chemonitoring.tools/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/chemstructures-by-moa-9-25-2023.xlsx

Brief summary of the history of pesticide use and initial concepts of mode of action

Pesticide use appears to date back to at least 2500 years BCE (reported use of sulfur by the Sumerians). Pliny the Elder writing centuries later noted plant materials and burnt ashes by the Romans (470 BCE -77 CE ) and possible use of arsenic. Chinese use of arsenic (900 CE), and nicotine (1494-1825 CE) following importation of tobacco to Europe.

Natural vs synthetic materials

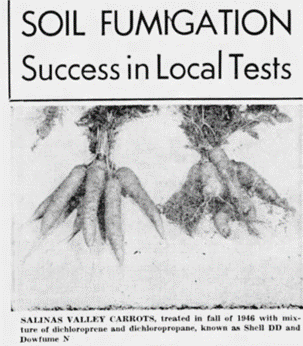

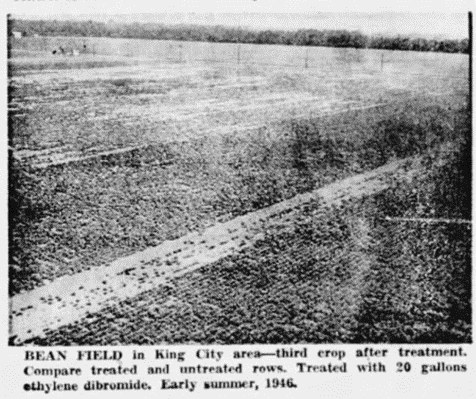

Inital attempts at chemical synthesis began in the 19th century (Hexachlorocyclohexane [HCH] 1824;– tetraethyl pyrophosphate [TEPP]- 1854; DDT 1874) and use of pyrethrum became widespread during the same period (e.g. commercial cultivation in Stockton, Ca , 1876). By the end of the century paris green and other arsenicals became common, including use to combat a midwestern outbreak of the striped (Colorado) potato beetle (1876).

Site of contact

Descriptions of insecticide mode-of-action focused on the initial site of contact with the insect target, typified by the terms “contact poison” and .“stomach poison”. This changed with the discovery of nervous system transmitters in the early 20th century

Mode of molecular and biological action as a concept: discoveries in physiology and chemical synthesis

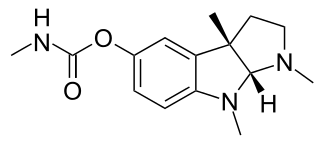

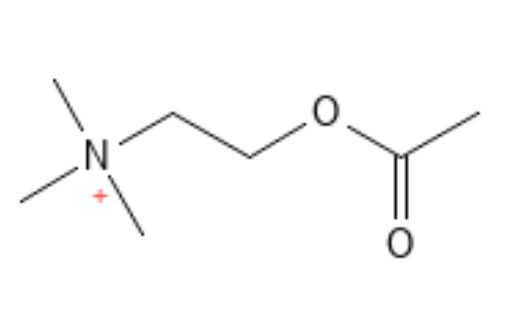

The discovery of ChE inhibitors resulted from isolation of natural compounds contained in the Calabar bean (1846), identification of the acetylcholine as a neurotransmitter , the cholinesterase enyzme that regulates its action (1913), and synthesis of synthetic compounds that blocked (inhibited) its action. This made clear for the first time that a broad group of chemicals shared a common mode of action (in the resistance classification, designated as IRC-1).

The section below review evidence for mode of action for ChE-inhibitors and sodium channel modulators (pyrethroids and DDT), along with known and potential effects on secondary biochemical targets.

For some groups of compounds, the process of separating the principle MOA from secondary effects remains a continuing challenge. Advances in molecular biology, genomics, proteomics, and bio-informatics have recently provided new information on pest target receptors and resistance mechanisms.

Timeline of reports in scientific journals

In 1846, WF Daniell, a Scottish military physician previously stationed in Western Africa, described to the Edinburgh philosophical society an ordeal poison used in the Calabar region of Nigeria, (WF Daniell biography and papers, RW Nickalls, Nickalls.Org)

The government of the Old Calabar towns is a monarchical despotism rather mild in its general character, although sometimes severe and absolute in its details. The king and chief inhabitants ordinarily constitute a court of justice, in which all country disputes are adjusted, and to which every prisoner suspected of capital offences is brought, to undergo examination and judgement.

If found guilty, they are usually forced to swallow a deadly potion, made from the poisonous seeds of an aquatic leguminous plant, which rapidly destroys life. This poison is obtained by pounding the seeds and macerating them in water, which acquires a white milky colour. The condemned person, after swallowing a certain portion of the liquid, is ordered to walk about until its effects become palpable. If, however, after the lapse of a definite period, the accused should be so fortunate as to throw the poison off from the stomach, he is considered as innocent, and allowed to depart unmolested. In native parlance this ordeal is designated as “chopping nut.” Decapitation is also practised, but not so much amongst criminals as the former process, being more employed for the immolation of the victims at the funeral obsequies of some great personage. Drowning is sometimes resorted to as a substitute for the first means of destroying life.

Fraser (J Anat Physioloy, 1864), an assistant to the professor of of Materia Medica of the University of Edinburgh reviewed numerous experiments on the effects of the Calabar bean in England and Scotland, and related controversies (see extract below).

While it may weaken the heart’s power, it neither stops the circulation nor arrests the heart’s action: in fact, that the mechanism of death by Calabar Bean is very much the same as that by either curare or conia . The result of my investigations obliges me to express my nonconcurrence with Dr Harley’s conclusions. Calabar Bean causes death by asphyxia; but the most careful examination has failed in shewing me that this asphyxia is due to a paralysis of the motor nerves.

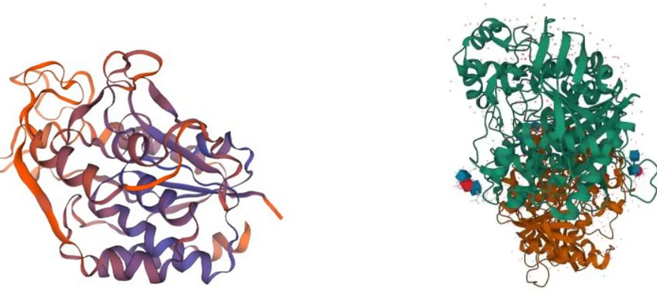

Advamces in structural chemistry and biology: Protein structures with complete amino acid sequencing, complemented by 3 dimensional imaging: Human NTE-lysophospholipase swiss model based on complete human amino acid and genetic sequence reported by Richardson etal Advances in Neurobiology 2020 PMID : 32518884; Franklin, M.C. et al , Proteins (2016) PubMed: 27191504 PDB model of human AChE based on Xray diffraction of purified 542 AA residue sequence, inhibited by para-oxon, bound anti-dote 2PAM

Devlopements in chemistry and physiology became pertinent to understanding of nerve agents synthesized in Germany and post-war insecticides. The stereotypical pattern of symptoms observed with physostigmine became a practical problem for chemists who first discovered synthetic pathways for oUrganophosphates, as discussed below.

Poisoning of chemists who discovered synthetic pathways for organophosphates

Lange & Krueger (1932) worked on synthesis of the methyl & ethyl esters of monofluorophosphoric acid. The researchers recognized their initial success as a pleasant and aromatic odor, followed within minutes by a sensation of pressure in the larynx, shortness of breath, mental confusion, and eye pain.

Gerhard Schrader began work for Bayer Laboratories plant protection division in 1934, charged with the task of developing a compound to develop new grain fumigants (replacing the reactive compounds then in use – ethylene oxide and methyl fumarate). Following the lead of Lange & Kruger, he synthesisized numerous phosphorous compounds, including a compound showing activity against leaf lice when diluted to a concentration of 0.2%. Subsequently his group created hundreds of variants, including an organophosphate with a nitrile substituent, termed preparation 9/91.

The preparation killed lice at concentrations 100 times less than the initial model compound but also proved extremely hazardous. After its initial synthesis in November 1936, Schraer became ill with poor concentration, headache, shortness of breath, dimming of visual fields, difficulty with accommodation, and pupils that failed to dilate in low light. Despite precautions, symptoms recurred when work recommenced on the synthesis. Tests with multiple animal species showed nausea, vomiting, constriction of the pupils and the bronchial tubes of th e lungs, copious drooling and sweating, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, muscular contractions and seizures.

The preparation [also known as Le-100, by military code names {Gelan, Trilon-83, T83} and as Tabun {CAS # 77-81-6}} was too toxic for use as a commercial insecticide. However Bayer’s parent company, IG Farbern, suggested to the German government that the compound had potential as a nerve agent. (War of Nerves, Chemical warfare from WW I to Al Qaeda:JB Tucker 2006 -a summary of German military archives and other sources).

Schrader’s group produced additional high toxicity compounds for potential military use. (Sarin –1938, Soman –1944 and cyclosarin –1949). Low level symptoms occurred in personnel testing nerve gas munitions. After the war, Schrader’s group produced the compound p-Nitrophenyl diethyl thiophosphate (parathion), first marketed as an agricultural insecticide in 1947. Systematic testing of parathion showed the stereotypical pattern of signs identified in animal tests of tabun, correlated with marked inhibition of ChE (1949).

Secondary effects

Despite the clear cut biochemical and clinical effects of ChE-inhibitors, years of subsequent work showed in vitro, in vivo and human effects related to secondary biochemical targets. These include NTE -LysoPLA, (summarized by Pope, Tanaka and Padilla, 1993 ) and butryrl cholinesterase, (summarized in Anderson et al 2019 PMID PMID: 30600548) both associated with recognizable clinical syndromes.

Butyryl ChE, metabolizing xenobiotics in the bloodstream (e.g., cocaine, succinyl choline and related compounds) proved very sensitive to inhibition by many OP compounds. BuChE genetic variants cause severe post-operative muscle weakness in patients administered succinylcholine as a muscle relaxant.

At various in vitro concentrations OPS inhibit other serine hydrolases (fatty acid amide hydrolase [faah], arylformamidase [afmid], and acylpeptide hydrolase [aph)]). Cellular signaling disruptions occur related to inhibiton of carboxylesterases, lipases, amidases, aph neuropeptide metabolism, afmid teratogenesis,, and interactions with the cannabinoid cb1 receptor.

Many OPs (diazinon, diazoxon and monocrotophos ) and a methylcarbamates (physostigmine, carbaryl) inhibit arylformamidase (AFMID), blocking the synthesis of nicotinic acid, causing potential malformations. Other OPs, including, parathion induce vertebrate malformations directly through inhibition of AchE .

OPs can inhibit carboxylesterase, amidases and “pyrethroid esterases” important for the metabolism of pyrethroids, effectively acting as insecticidal synergists, with possible similar effects in mammals.

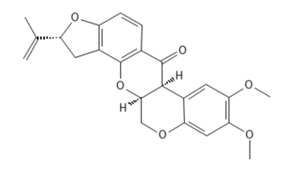

Pyrethrum, pyrethrins, and pyrethroids, historical use, physiology and mode of action studies

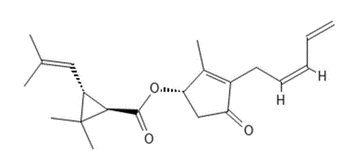

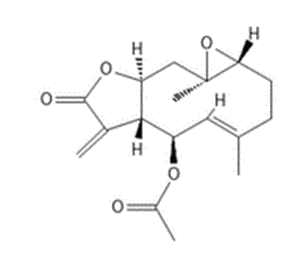

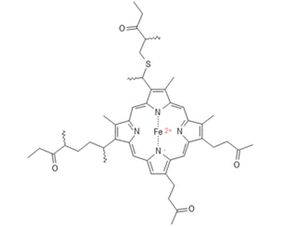

PCID 5281496 CAS # 28272-18-6

Physiologic advances in the 19th century included the first description of the nerve action potential (1848) and a refinement by Bernstein in 1868 measuring the axon conduction velocity with an instrument he called a rheotome or “current slicer”. The use of pyrethrum became very common in the 2nd half of the century in both US and Europe (See pesticide history spreadsheet down load link below).

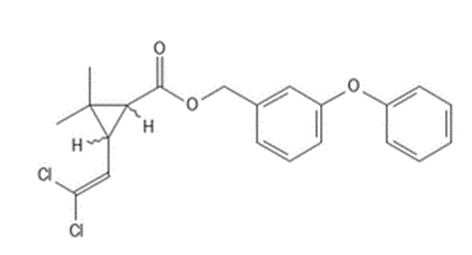

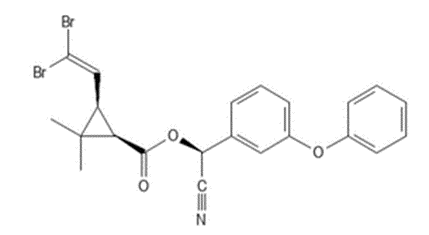

Natural Pyrethrins and pyrethroids.

In 1902, Bernstein described the membrane hypothesis for the action potential, based on equations describing electrical physics by Nernst and the physical chemistry of semipermeable membranes by Oswald . Although he correctly related the axon electrical activity to ion flux, he felt the active ion was potassium.

Between 1910 and 1916, Staudinger and Ruzicka prepared about 100 candidate pyrethroids although none proved to be potent insecticides. In 1944, LaForge and Barthel demonstrated minor errors in the projected structures and in 1949 reported synthesis of the first synthetic pyrethroid allethrin.

In 1942 Lowenstein develsoped an assay for pyrethrum in solution based upon duration of an action potential measured with an electrode in a cockroach ventral nerve. Subsequent single nerve axon electrode studies by Hodgkin and Huxley (1945) showed the nerve action potential diminished with low external sodium concentrations but did not change with variations in potassium or substitution of the sulphate anion for chloride.

Narashi and Anderson (1967) showed that allethrin affected the action potential in a manner very similar to pyrethrum.

Systematic animal studies in the 1970’s demonstrated unique neurologic symptoms associated with pyrethroids, distinguishing between type I compounds similar to allethrin and a newly created type II cyanopyrethroids (Costa 1980). By the 1980’s understanding of the physiology of the sodium channel progressed with determination of the trans-membrane sodium channel protein structure (Noda 1984).

Genetic studies of the channel correlated mutations in protein cytoplasmic domains with increased insect resistance to the “knockdown” properties of pyrethroids. Studies using various radiolabeled toxins (tetrodotoxin, veratridine or batrachotoxin) have identified binding sites “allosteric” (protein binding affecting the conformation of the main binding site) .

Sodium channel receptors exist in all parts of the mammalian nervous system. Occupational exposure to pyrethroids often produces dermal paresthesias without minimal visible skin reaction. Following case reports by (LeQuesne, 1980) , studies by Flannigan and colleagues (1985) demonstrated induction of skin paresthesia in human volunteers after experimental applications of fenvalerate, cyfluthrinate, permethrin, and cypermethrin.

Topical scopolamine had no discernible effect on the sensation of paresthesia, evidence if needed that the paresthesia did not result from anti-cholinergic mechanism. Vitamin E oil applied topically markedly decreased the paresthesia for all 4 pyrethroids tested (91% by the protective index used in the article), but mineral oil (68.3%) and A&D ointment (74.1%) also provided substantial protection The authors suggested the benefit of Vitamin E derived from its antioxidant properties, although the antioxidant preservative Butylated Hydroxyanisole showed no protective effect (8.4%).

Pharmacologic agents targeting the sodium channel include local anesthetics, anti-epileptics, and anti-arrhythmics (Channels, Austin, 2015; Goodman & Gilman, 2017).

Pyrethroid secondary biochemical targets

The number of secondary biochemical targets for pyrethroid identified to date appears limited compared to the list for the ChE-inhibitors. Evidence includes biochemical and in Vitro studies showing possible stimulation of voltage-gated calcium channels, voltage-gated chloride channels, and GABA A receptors ( Soderlund et al. , 2002 ). No evidence exists for animal in Vivo or human clinical effects related to these secondary ion channel targets

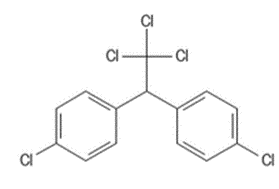

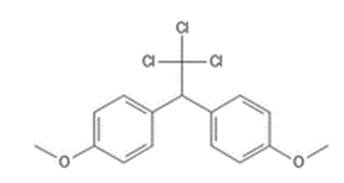

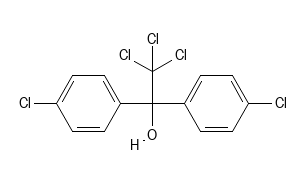

DDT and related compounds as sodium channel modulators

When Paul Hermann Müller reported the insecticidal action of DDT in 1939 its mode-of-action remained undiscovered. In 1970, Hayes described the difficulty of attributing the same mechanism to chlorinated hydrocarbons with markedly differing structures (e.g., chlorinated cyclodienes and DDT-analogues).

The chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides have in common the chemical composition implied in the group name. However, beyond this broad similarity, the compounds vary widely in chemical structure and activity. Although much is known about the pharmacology of these materials, the basic mode of acti on is not known for a single one of them. It is entirely possible that chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides of significantly different chemical structure have different modes of action; it is certain that there are qualitative as well as quantitative differences in their pharmacologic action.

Van den Bercken applied the single axon electrode technique that demonstrated the sodium channel mechanism of the pyrethroids (1967) to study of the organochlorines and dieldrin and DDT in 1972. The results for DDT closely resembled those for the pyrethroids, but dieldin showed no activity in the assay. Hayes (1982) cited the 1972 paper by Van den Bercken and its effects on axon membranes. The distribution of sodium-channel receptors throughout the mammalian nervous was not known for many years, so it was not immediately clear whether the Van den Bercken results explained DDT’s CNS effects as well as its effects on the peripheral nerves.

Hayes also noted minimal effects in many studies in human volunteers and results of deliberate overdose. Deliberate skin contact did not produce the paresthesias seen with pyrethroids (ATSDR p 105/ 486 – labeled page # 93 upper R corner; Hayes 1982), but paresthesias occurred in poisonings following accidental or deliberate poisoning.

Secondary biochemical targets

The secondary effects of DDT have at times led to confusion about its primary mode of action. Carson (1962), for example, noted laboratory reports on DDT causing an uncoupling of oxidative-phosphorylation, suggesting it caused the reproductive problems noted in bird populations (Carson, 1962). Journal publications discussing the effect of DDT on oxidative phosphorylation include Byczkowski (1976) and Elmore & La Merril, (2019), describing impairment of oxidative-phosphorylation at multiple steps in mitochondrial electron transport. The 1976 paper suggested that the mitochondrial effects of DDT could cause some symptoms of acute poisoning.

Hayes (1982) noted the capacity of DDT to induce hepatic enzymes. Smith (2010) suggested that the adrenal mitochondrial effect of DDT occurs secondary to enzyme induction, as well as possibly underlying its hepatic carcinogenicity in animal feeding studies.

High concentrations of DDT inhibit phosphatidase, muscle phosphatases, carbonic anhydrase and oxaloacetic carboxylase. They increase the activity of cytochrome oxidase and succinic dehydrogenase. None of these changes, with the possible exception of inhibition of carbonic anhydrase, may have any connection with the principal toxic action of DDT or even with its secondary effects

The mechanism of egg-shell thinning demonstrated empirically in DDT feeding studies probably relates to an indirect estrogenic effect, reducing, levels of pituitary carbonic anhydrase (demonstrated in Japanese quail – equivocal in poultry). Other possible chronic effects of DDT relate to its estrogenic effects, environmental persistence and its propensity to accumulate in the food chains (Pine River statement, 2009 Eskenazi et al).

MOAs for multi-site activity compounds

History

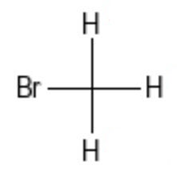

Methyl bromide chemid 6323 -cas # structure drawn with pubchem – dpr chemcode, chem number (1974) 385 EPA PC code – 053201

An NIH review of methyl bromide toxicology published in Public Health Reports (1940) cited the reports Richardson reports discussed below and may have influenced subsequent reviews regarding its mode of action.

The Victorian physician Benjamin Ward Richardson described a method for synthesizing methyl bromide (Practitioner 1871):

“a gas made by mixing at a low temperature fifty parts of bromine, two hundred of methylic alcohol, and seven of phosphorus. By using cold the ether can be distilled over as a fluid, but it boils at 55° Fahd. and is therefore at ordinary temperature a gas. Its vapour density is 48. Bromide of methyl, like bromide of ethyl, is an anaesthetic equally effective as the latter, and sharing in all its faults.”

In an 1891 publication, Richardson reported on secondary effects from its use as an anesthetic:

METHYL-BROMIDE, a sharply-acting general anesthetic, the analogue of ethyl bromide in the ethane series, has lately been, it is reported, the cause of death in several cases in which it has been administered. As it acts with great rapidity, it has gained some favour in dental practice ; but, of necessity, with considerable risk. Ethyl bromide, first used by the late Mr. Nunnerley, of Leeds, and afterwards by myself, was discarded because of its danger ; yet it is safe in comparison with the lighter methyl bromide. The danger, as I have pointed out more than once, lies in the instability of these compounds. They decompose readily, and may permit free bromine to be liberated during inhalation, an accident followed by rapid spasmodic contraction of both the pulmonary and coronary arteries, with death by syncope of both the lesser and the greater circulations.

Such accidents afford, unfortunately, the best proof of the folly of using any general anesthetic, until, by careful experiment, the precise action of the substance has been determined. To practise first on human beings with agents so potent as these is the empirical method carried to recklessness, and ought really to come under the correction of law.

Comments:

Reactivity of ionized fluoride vs bromide

The role assigned to the bromide ion by Richardson proved incorrect, but subsequent work has showed that fluoride acts much as Richardsonb described – liberated by metabolism of sulfuryl fluoride or ingestion of sodium fluoride. Fluoride possesses greater electronegativty than bromide and reacts immediately with serum or tissue calcium.

Anesthesia or sedation as mode of toxic action

Anesthesia or depression of respiration does not explain symptoms related to repeated exposures (Hine 1969 – J Occup Med . 1969 Jan;11(1):1-10. PMID: 5771232) without producing any episode of lost consciousness. (O’Malley et al 2010 Likewise, short term exposures that do not produce initial unconsciousness produce severe secondary effects result from the toxic effects of fumigant on multiple organ systems ( Price 1992,O’Malley, 1997 Lancet; Horowitz et al J Tox Clin Tox 1998; Li et al, Int J Medical Research:, 2022)..

Methyl bromide as an alkylating agent

An NIH review of methyl bromide toxicology published in Public Health Reports (1940) cited the Richardson reports and may have influenced subsequent reviews regarding its mode of action. Lewis (1944) that reported methylation of enzymes by methyl bromide, regarded as by possible primary MOA in many subsequent publications He also cited a paper (Loveday and Winteringham 1951, ishimura rr ~1.. 1980, Starratt and Bond, 1981, Alexeeff & Kilgore 1983)

MeBr affects on enzymes and other proteins

Molecular targets suggested for methyl bromide include glutathione and the enzymes triose phosphate dehydrogenase (aka GADH), succinate dehydrogenase, and creatine kinase. de Souza (2014) reviewed neurological effects of methyl bromide and discussed whether intermediate metabolites, such as methanethiol, might prove the active toxic agent. He also noted the direct effect of methyl bromide in inhibiting creatine kinase, disrupting oxidative phosphorylation and decreasing the level of tyrosine hydroxylase, a key enzyme in the synthesis of dopamine.

Reactive oxygen species

A very recent study noted the effects of methyl bromide on plants, using Arabidopsis thaliana (Thale kress, a flowering weed common in Asia) as a model. Kim et al (2021) described changes in gene transcription after either 2 or 4 hours exposure of Aradopsis plants to methyl bromide. For 7 days they measured subsequent changes in gene transcription as well as differences in appearance, growth and physiologic factors related to phytoxicity (plant auxin and anthrocyanin production), and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

The authors used Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes (KEGG pathways) and Genome Ontogeny (GO – biological process) databases to categorize the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in pre-and post fumigation gene activity. Plants treated for 2 hours did not differ significantly from controls in terms of physical appearance compared to controls, but plants treated for 4 hours had significantly less stem growth by day 7, showed a lower plant health score and many had withered significantly. The content of anthrocyanin (a measure of plant stress) increased and plant auxin decreased. A comparison between 4 hour fumigated plants to controls showed significant differences for 620 upregulated and 753 downregulated genes.

The top KEGG pathways for both 2 hour and 4 hour compared to controls included signal transduction, carbohydrate metabolism, environmental adaptation, and folding, sorting, and protein degradation.

For the comparison between 4 hour fumigation plants and controls, glutathione metabolism (MapID 00480) and spliceosome (MapID 03040) were highly upregulated, glycine, serine, and threonine metabolism (MapID 00260), glucosinolate biosynthesis (MapID 00966), and ABC transporters (MapID 0201) were downregulated in the MB-4h treatment (Table 1 and S6). The GO analysis identified 55 biological processes (BPs), including response to abiotic and oxidative stress with p < 0.0001. (55.6%).

Identified ROS included multiprotein bridging factor 1 (MBF1c). heat shock transcription factor A1E (HSFA1E). key regulators of transcriptional cascades related to heat shock and abiotic stress in A. wothaliana. This produced expression of heat shock proteins (HSPs), heat shock transcription factors (HSFs), and glutathione S-transferases (GSTs). The authors predicted the fumigation of MB would cause severe cellular oxidative stress in the chloroplasts, mitochondria, and ER, along with cell apoptosis. in individuals of A. thaliana. The fumigations did not directly alter the concentration of plant auxins, but did lower the concentration of auxin transport proteins. The report described in both detail and in a broad perspective the many biologic effects of methyl bromide.

Does work on Aridopsis predict affect on animals and other plants?

To this point, no similar research has demonstrated that ROS occur in mammals poisoned by methyl bromide. Although the specific ROS and KEGG pathways might differ, it seems appropriate to generalize the work on aridopsis to mammals.

Mitochondrial Energy metabolism

Mitochondrial ATP synthase inhibitors, IRC 12

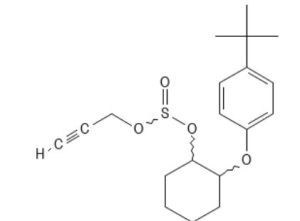

Responsible for numerous episodes of eye and skin irritation, propargite accounted for a high percentage of miticide use prior to development of alternative AIs.

Propargite PCID 4936 MF: C19H26O4S MW: 350.5g/mol

Secondary effects likely related to propargyl derivative containing a reactive unsaturated triple bond.

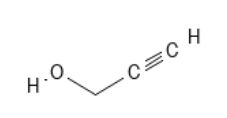

Propargyl alcohol – PCID 7959, likely intermediate metaobolite based upon propargite DPR risk assessment

MF: C3H4O MW: 56.06g/mol

Safety warnings related to propargyl alcohol

Propargyl bromide PCID 7842, a reactive compound considered as alternative to methyl bromide, rejected related to safety issues

Mitochondrial complex IV electron transport inhibitors (IRC 24), cytochrome oxidase, phosphine, phosphide and cyanide compounds.

Thomas Oxley -identification of derris roots J Indian Archipelago 1848 “Some Account of the Nutmeg and its Cultivation

The Planter having selected his seed, which ought to be put in the ground within 24 hours of being gathered, setting it about 2 inches deep in the beds already prepared, and at the distance of from 12 to 18 inches apart, the whole nursery ought to be well shaded both on top and sides, the earth kept moist and clear of weeds, and well smoked by burning wet grass or weeds in it once a week, to drive away a yery small moth-like inect that is apt to infest young plant, laying ita eggs on the leaf, when they become covered with yellow spots, and perish if not attended to speedily.

Washing the leaves with a deeoction of the Tuba [derris] root is the best remedy I know of, but where only a few plants are affected, if the spots be numerous, I would prefer to pluck up the plant altogether rather than run the risk of the insect becoming more numerous, to the tot.al destruction of lhe nursery.

Esposti (1998) described a variety of complex I inhibitors from broad categories including Annonaceous plants (acetogenins – Rolliniastatin), Vanilloids plants (Capsicum. Capsaicin) Myxobacterial antibiotics (Polyangium Phenoxan), neuroleptic drugs (haloperiodol) and synthetic neurotoxins (the meperidine contaminant MPP), and new insecticides (also described . Sparks et al, 2019. The insecticides, closely mimicking the function of rotenone, included fenpyroximate and pyridaben (1991); fenaquin and tebufenpyrad (1993); pyrimidifen (1995); and tolfenpyrad (2002).

The story of the role of cytochrome oxidase in electron transport begins with discovery of the cytochrome c substrate, originally reported by Macmunn in 1886, then independently isolated by Kellin in 1925

Kellin noted the presence of a pigment in the fly Gasterophilus intestinalis showing a 4 banded spectrum in the absence of oxygen but not detectable in its presence. He deduced that the agent differed from hemoglobin but also reacted with oxygen. He found the same behavior in extracts of yeast and noted that cellular respiratory poisons liked cyanide also blocked the cycle of oxidation and reduction for the substance. He eventually deduced that the cytochrome formed part of chain of reactions, acting in concert with the dehydrogenase factor, inhibited by urethane but not by cyanide. In a 1977 paper in Nature Wikstrom reported on the coupling of cytochrome c oxidase to the transfer of protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane storing energy in the transmembrane electrical potential.

Leave a comment