Disruptors of insect energy metabolism – schematic 2015 biochem reference Chapter-13—Electron-Transport-Chain–OxPhos.pdf; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rotenone

Many current insecticides target insect energy metabolism, principally by interfering with the action of mitochondrial enzymes and the synthesis of ATP.

The newer agents generally have very selective effects on target enzymes, but a few very reactive older agents have many secondary effects. The major biochemical processes affected occur in mitochondria in the electron transport chain. Specific targets include lipid membranes and membrane bound proteins.

Mitochondrial electron transport MOAs

Thomas Oxley -identification of derris roots J Indian Archipelago 1848 “Some Account of the Nutmeg and its Cultivation

The Planter having selected his seed, which ought to be put in the ground within 24 hours of being gathered, setting it about 2 inches deep in the beds already prepared, and at the distance of from 12 to 18 inches apart, the whole nursery ought to be well shaded both on top and sides, the earth kept moist and clear of weeds, and well smoked by burning wet grass or weeds in it once a week, to drive away a yery small moth-like inect that is apt to infest young plant, laying ita eggs on the leaf, when they become covered with yellow spots, and perish if not attended to speedily.

Washing the leaves with a deeoction of the Tuba [derris] root is the best remedy I know of, but where only a few plants are affected, if the spots be numerous, I would prefer to pluck up the plant altogether rather than run the risk of the insect becoming more numerous, to the tot.al destruction of lhe nursery.

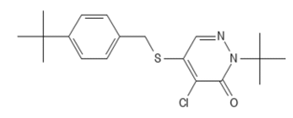

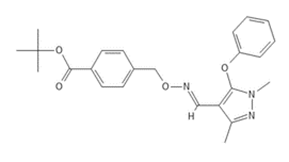

Esposti (1998) described a variety of complex I inhibitors from broad categories including Annonaceous plants (acetogenins – Rolliniastatin), Vanilloids plants (Capsicum. Capsaicin) Myxobacterial antibiotics (Polyangium Phenoxan), neuroleptic drugs (haloperiodol) and synthetic neurotoxins (the meperidine contaminant MPP), and new insecticides (also described . Sparks et al, 2019. The insecticides, closely mimicking the function of rotenone, included fenpyroximate and pyridaben (1991); fenaquin and tebufenpyrad (1993); pyrimidifen (1995); and tolfenpyrad (2002).

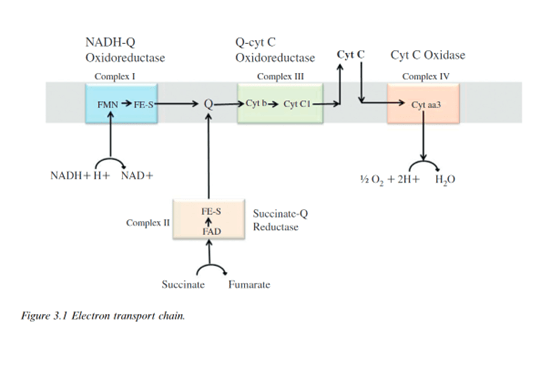

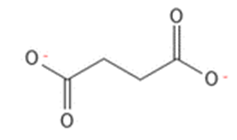

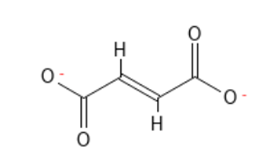

Complex I oxidizes NADH and reduces the carrier molecule ubiquinone – coenzyme Q – acting as the substrate. In a parallel process, complex II converts succinate to fumarate, also generating reduced ubiquinone. Complex III oxidizes reduced ubiquinone while reducing cytochrome b to cytochrome c. Complex IV – oxidizes cytochrome C – to cytochrome aa3. ATP-synthase uses the proton gradient created in the transport chain to energize synthesis of ATP from ADP

Active ingredients targeting electron transport include some individual reactive compounds (see complex I & complex IV inhibitors) along with new families of AIs in each IRC group with very favorable safety profiles.

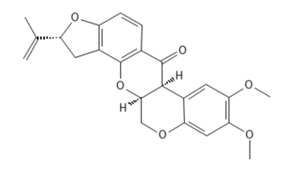

Mitochondrial complex I electron transport inhibitors IRC 21 – rotenone and Cubé, fenazaquin, pyridaben, tolfenpyrad – possibly interfere with binding of the substrate coenzyme Q, aka ubiquinone.

PCID 91754 CAS # 96489-71-3

The 1974 data did not show use of any complex I inhibitors. The 2016 use data showed 53,159.6 lbs sold, 0.026% of total, 51866.3 lbs reported use, 0.037% of total, 7315 applications, 0.56% of total, and 275764.0 acres treated, 0.72% of total.

Registration data showed a total of 211 rotenone products registered between 1981 and the present, but only 2 registered in 2016.

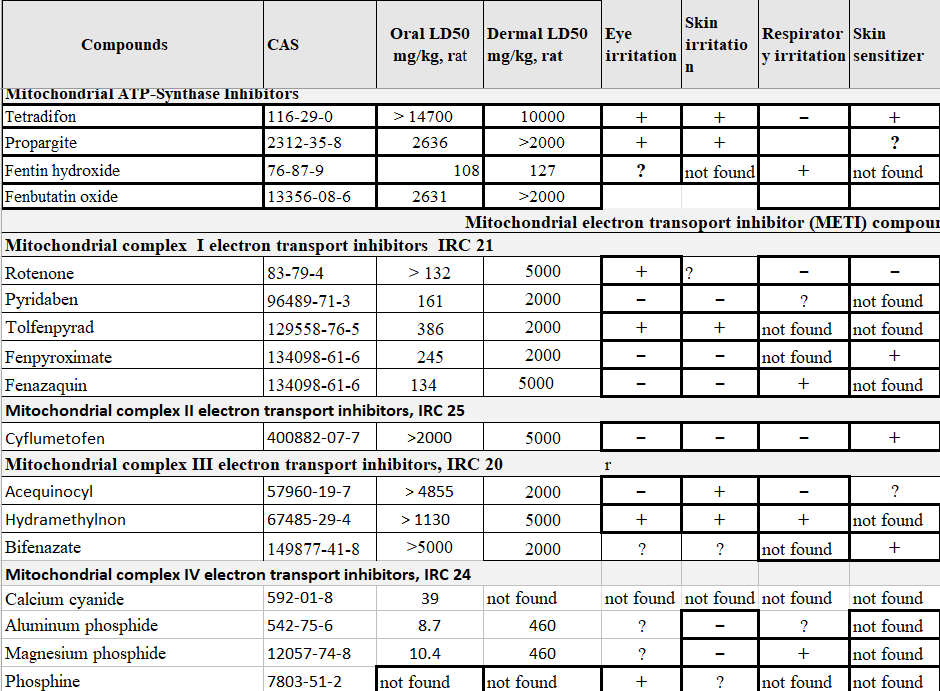

The table below shows acute toxicity of compounds affecting mitochondrial electron transport chain

Complex I inhibitors have moderate acute oral toxicity, but limited systemic toxicity with skin contact (Table 5). Non-systemic effects at the point of contact include conjunctivitis, dermatitis, sore throat, and congestion. Formulations containing naphthalene range aromatics have a distinctive “mothball” odor prone to cause non-specific systemic symptoms (see below).

1992- 2017 illness data show 22 reports associated with fenpyroximate as the only implicated pesticide. 21 cases resulted from accidental exposure to field workers who entered a field during an application of fenpyroximate (47-MON-10). Multiple workers reported included non-specific systemic symptoms and/or irritation of the eyes or the upper respiratory system (Table 3b). A Kern county field worker reported skin irritation after mist from an application about 40 feet away landed on his forehead.

Between 1992 and 2017 62 cases occurred associated with isolated exposure to rotenone, all related to its 1997 use to eliminate invasive northern pike in Plumas County. Symptoms included non-specific systemic symptoms, eye and respiratory irritation in Lake Davis residents (1997, Table 3b).

Literature reports in Table 3b demonstrate that fatal poisoning can occur after ingestion of rotenone. Case examples illustrating typical severe symptoms (loss of consciousness, nausea, vomiting etc) associated with acute ingestion include reports from French Guinea (2009) and French Polynesia (2017).

Three reported pyridaben cases occurred, involving handlers with dermatitis (999-1189), eye irritation (2001-34), or mild systemic symptoms associated with an odor (2003-519).

Mitochondrial complex II electron transport inhibitors, IRC 25 cyflumetofen (chem code 6083, initial product registration – 2014)

After Sasama reported the first synthesis of cyflumetofen in 2007, it became registered in Japan. Hayashi (2013) demonstrated that it inhibited mitochondrial respiration at Complex II (succinate dehydrogenase). California first registered technical cyflumetofen (7969- 335, 98.6% ai) in 2014 and two agricultural use products (7969- 336, 7969- 337) in 2015. Target species include web forming spider mites (Tetranychidae), and other plant eating mite families (Tenuipalpidae,

Eriophyidae, Tarsonemidae and Tuckerellidae). Cyflumetofen does not affect Lepidoptera, Orrthoptera, Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, and other common agricultural pests.

2016 use data show for cyflumetofen 126,023 lbs sold (0.034% of total), with 70172.4 lbs of reported use (0.050 % of total), 7112 applications (0.054% of total) on 380,117 treated acres (0.55 % of total). Analysis of 7150 individual records show 18 non-agricultural and 7132 agricultural application sites.

Table 5 shows low mammalian toxicity and the absence of common secondary irritant effects in animal testing. Based upon a very limited period of post-market surveillance, no California illness reports identify cyflumetofen as the sole implicated pesticide. A search of PubMed did not identify any cases of deliberate or accidental poisoning (search term “cyfumetofen poisoning”).

Mitochondrial complex III electron transport inhibitors, IRC 20 (acequinocyl, bifenazate, and hydramethylnon)

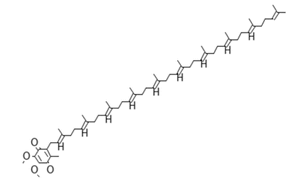

Dupont discovered acequinocyl in the 1970’s, but it was not marketed as an insecticide until the 1990’s. Koura (1998) demonstrated its action on the ubiquinol oxidation site (Q0) of complex III, activated by de-acetylation to 2‐hydroxy‐3‐n‐dodecyl‐1,4‐naphthoquinone (DHN). Van Leeuwen reported insect cross-resistance between bifenazate and acequinocyl, arguing that they act at the same or similar site. Binding studies with radiolabeled bifenazate confirmed . The first US EPA registration for technical acequinocyl occurred in 2003 (66330-39).

Lovell (1987) first reported the discovery of a series of amidinohydrazone compounds with activity against insects with chewing mouth parts (roaches and grasshopers) and those with sponging mouthparts (flies). Hydramethylnon emerged from this work, commonly marketed as a bait insecticide used against household insects. Hollingshaus (1987) described the effects of hydramethylnon on succinate dependent respiration (MET Complex II – succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase ). Song (2009) used hydramethylnon as a positive control in experiments evaluating the effect of formate esters on ubiquinol-cytochrome c oxidoreductase, reporting an LC50 for cytochrome C oxidase of 0.45 mM for hydramethylnon compared 1-2 mM for the other positive control, sodium cyanide. PPDB and the IRC classification both list hydramethylnon as a complex III inhibitor.

The 2016 data for the MET III complex inhibitors showed 89,517.8 lbs sold (0.044% of total); 171,109.1 lbs reported use (0.12% of total), 11,643 applications (0.89% of total), 506,158.0 q

Use data and registration data show use of hydramethylnon for structural pest control rather than for agricultural products. 30 of 114 historically registered products had active registrations in 2016. Agricultural applications accounted for 162 (4%) of 4,003 individual applications reviewed, principally ant bait products also used for structural pest control. Crops treated included ornamentals and almonds.

3 acequinocyl products with 15.8 % AI had use in 2016 as miticides on citrus, nut trees, ornamentals, grapes, berries, tomato and peppers. For 2104 individual applications, the average rate equaled 0.32 lbs per acre. 12 bifenazate products had use in 2016 with 98% of the applications for agricultural use. For 9664 individual applications, the average rate equaled 0.51 lbs per acre.

Toxicity and illness data

All 3 MET III complex inhibitors have low acute mammalian toxicity (Table 5). Animal tests, typically performed on concentrated technical formulations, show hydramethylonon can cause eye, skin and respiratory irritation. Data for acequinocyl and bifenazate appear less clear cut. The bait products for ant and roach control typically have AI concentrations less than 1%, so the test results on the technical may not prove relevant. The PPDB data show bifenazate as a potential dermal sensitizer, in agreement with the labeling on several products registered or previously registered in California (91234- 20-AA- 83520; 400- 508-AA- 59807; and 400- 508-ZA).

The California illness registry showed a total of 7 cases with MET III group compounds as the only implicated AI. 4 pediatric hydramethylnon cases involving attempted ingestion of bait products, each followed by possibly related short term episodes of vomiting (Table 3b). An adult case following accidental ingestion also resulted in gastric symptoms. 1 case of contact dermatitis involving bifenazate (2004) and a similar case involving acequinocyl (2009) resulted from accidental direct exposures to agricultural pesticide handlers.

A pubmed literature search for poisoning cases involving bifenazate, acequinocyl or hydramethylnon did not identify any reported cases.

Mitochondrial complex IV electron transport inhibitors (IRC 24), cytochrome c oxidase, phosphine, magnesium and aluminum phosphide, and calcium cyanide.

Chefurka, Kashi and Bond (1976) described the effects of phophine gas on mitochrondrial respiration. Kinetic studies showed inhibition of cytochrome oxidase at molar concentrations 1.6X10-5 to 7.2 X10-7 just above the lowest range reported for inhibition by sodium cyanide (10-8) (Erecinska and Wilson, 1980). Other gases affecting cytochrome oxidase included carbon monoxide and nitric oxide, fluoride ion, hydrazine, azide, and others acting at molar concentrations as low as 10-7. Formate, fluoride and sulfide require molar concentrations between 10-3 and 10-2.

Phosphine has possible secondary effects. In vitro studies show it may also inhibit catalase, causing intracellular peroxides to increase (Garry, 2010). Proudfoot (2009) echoed this point, suggesting that in Vitro effects of phosphine on cytochrome oxidase may prove less important than oxidative stress in mammalian poisoning. A 2000 paper by Jian underlined these points demonstrating significantly less in vivo (30.8 vs 20.9 33%) compared to in vitro inhibition (30.8 vs 17.6 3h 13.2 6h) 50%) of cytochrome oxidase in treated copra mite adults (Tyrophagus putrescentiae) compared to controls, For catalase in vitro inhibition (14.10 vs 10.84 3 h vs 7.70 6h) less than in vivo inhibition (14.10 vs 7.15 6h ) p 5/7 table 2

US EPA data show the first registration date for aluminum phosphide in 1958 (72959-1), for magnesium phosphide in 1979 (72959-6), and phosphine in 1999 (68387-7). EPA data show the earliest registration of calcium cyanide (241-5) as 1947 and the cancellation date as 1985.

Total use of complex IV AI’s for 1974 equaled equaled 5323.7 lbs (0.0093% of total insecticide use). This included 155.1 lbs of calcium cyanide and 5168.6 lbs of aluminum phosphide. Review of individual application data for calcium cyanide found 140 applications of a single formulation of calcium cyanide ( 241-5), labeled for use in vertebrate pest control (mice and rats, groundhogs) and for control of ground nesting yellowjackets.

Of the 238 reported applications of aluminum phosphide, 195 records showing treatment for unspecified institutional purposes accounted for 81.9%, 18 records for structural pest control accounted for 7.6%, and 25 records showing treatment of agricultural commodities accounted for 10.5%.

For 2016 Complex IV AIs with reported use included phosphine gas, magnesium phosphide, and aluminum phosphide for a total of 362,304.1 lbs sold, 355,963.7 reported lbs used, and 11,566 applications. Records for 7580 individual applications showed 96% of the use for commodity fumigation. The 41 reported products included 31 containing aluminum phosphide, 6 containing magnesium phosphide, and 6 containing phosphine gas mixed with 2% carbon dioxide.

Toxicity and illness data (Table 5 ) show the high oral toxicity of aluminum and magnesium phosphide, phospine and cyanide. Because the phosphide salts release phosphine gas on contact with air or water, most exposure occurs by inhalation. However, direct contact of phosphide salts with moist skin or mucous membrane can probably cause release of phosphine and secondary irritant symptoms. Air concentrations of phosphine greater than 2% present a risk of fires or explosions. In practice the safety hazard occurs when phosphide salts react with moisture. Presence of 2% CO2 effectively mitigates the possible risk associated with phophine gas cylinders. Ammonium carbamate contained in most phosphide salt formulations partially stabilizes aluminum phosphide, breaking down to ammonia and carbon dioxide

Safety issues

The chemical instability of phosphine gas in contact with air and watetr has led to multiple safety issues with use of aluminum phosphide in commodity fumigation (1993, 1998, 2009, 2013 Table 3b). documented by a NIOSH in a 1999 safety alert (NIOSH, 1999) and a later journal publication (O’Malley, 2010). Since initial California registration in 2001, surveillance data has identified no episodes of fires or explosions associated with use phosphine gas formulated with CO2, containing 2% phosphine and 98% CO2. Summary California use data does not distinguish between the 2% phosphine formulation and a gas formulation initially registered in 2002 containing 99.3% phosphine.

Illness data

A 1973 annual illness summary briefly described the death a pest control worker who used calcium cyanide indoors without wearing a respirator (HS 40). A similar structural pest control death occurred in 1975, as well as a suicide reported the same year (Table 3b). The current illness records available online cover events in 1992 and subsequent years, well after calcium cyanide registration cancellation in 1985.

Between 1992 and 2017, California data showed 211 cases related to phosphine or phosphine-generating salts affecting applicators, warehouse grain inspectors and other bystanders, and emergency responders. These included 2 fatalities, both deliberate ingestion cases in 2003. In the second episode both emergency responders and coroner’s staff had secondary exposure (Table 3b). The fires, mis-applications, and deliberate ingestion case all resulted from obvious violations of required procedures for handling aluminum phosphide. Pediatric poisonings summarized in Table 3b included reports from Iran (2017). Utah (2011), Texas (2017), and China (2020). All resulted from household treatments or use adjacent to homes. In the Texas case, application of water after treatment of home subspace with aluminum phosphide tablets resulted in 4 pediatric fatalites and 15 secondary cases in emergency responders.

A 2014 risk assessment from Cal-EPA, based upon acute and chronic animal studies, proposed reference doses for 0.05 ppm for short-term exposure and 0.01 ppm for seasonal exposure. The existing 0.3 ppm permissible exposure limit (PEL) originally derived from the 1968 ACGIH TLV and limited related documentation regarding exposures from grain fumigations in Australia (Jones, 1964). In 2018 ACGIH adopted a new 0.05 ppm TLV, but the US OSHA PEL remains 0.3 ppm as does the NIOSH recommended exposure limit and the product labels on aluminum phosphide tablets and phosphine-CO2 fumigant gas.

ATP synthase inhibitors 1974, 2016 use data (organontin compounds, fentbutatin oxide, fentin hydroxide; propargite; tetradifon)

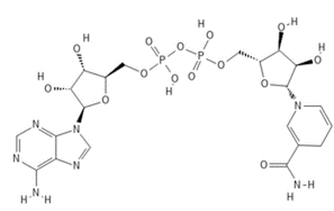

Karl Lohmann isolated adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from muscle and liver extracts in 1928 and deduced the structure after finding two moles of phosphoric acid,one mole of adenine, and one mole ofd-ribose-5-phosphate after acid hydrolysis. Fiske and Subbarow found a similar compound in I929. J. Baddileya, M. Michelson And A. R. Todd resolved controversy about structural details by synthesizing ATP in 1948. In 1960 Racker and co-workers isolated adenosine trisphosphatase (currently called ATP synthase). Subsequent work (Walker, 1984 Abrahams et al 1994, Zhou et al 2015) detailed its complex transmembrane structure (F0) and rotating catalytic (F1) mechanism (Boyer, 1989; Okuno et al 2011).

The complex ATP Synthase structure allow many possible sites for binding of inhibiting and modulating compounds. As its name implies the intrinsic F1 inhibitor binds between subunits of the catalytic F1 unit, regulating production of ATP (Garcia-Aguilar and Cuevza, 2018). The dicarbi-imide compound dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD 538-75-0), the antibiotics oligomycin, bedaquiline venturicidin and ossamycin. bind to the F0 site, blocking the rotary proton transport mechanism. Insecticides binding near this same location include diafenthiuron, and the organotin biocides.

Binding sites for some older insecticides thought to inhibit ATP-synthase remain to be established, including the most widely used reported inhibitor, propargite. In 1966 Uniroyal (US Rubber) received a patent for sulfite esters with insecticidal properties, and multiple propargyl derivatives in 1967. The first registration of propargite occurred in 1969. Its IRC classification identifies it as a mitochondrial ATP synthase inhibitor. It contains a highly reactive propargyl moiety, thought responsible for its secondary irritant effects on the eye and skin. IRC classifies propargite as an ATP synthase inhibitor, although accessible documentation could not be located. The pesticide properties database also describes it as an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation, as do some studies of its insecticidal efficacy (Pridgeon, 2008). Early et al (2019) noted that the existing evidence does not clearly show that in vivo effects of propargite results from inhibition of ATP-synthase. The proposed

ATP synthase inhibitor group AI’s in use during 1974 accounted for 800,756.4971 lbs of reported use, 1.4% of total use, nearly all due to propargite, with minimal use of fentin hydroxide, fenbutatin-oxide, and tetradifon. The average rate for 6,765 propargite applications equaled 1.98 lbs/acre. For 78 applications of tetradifon, the average rate equaled 0.67 lbs/acre and for 25 fentin hydroxide applications equaled 0.29 lbs/acre. Most frequently treated crops included cotton, nuts, citrus, stone fruit (peaches, nectarines, and plums) and apples.

2016 data showed 69,980.9 lbs sold, 0.034% of total; 213,204.0 lbs of reported use, 0.15% of total; 2,208 agricultural applications; and 92,814 treated acres 0.134% of total. AI’s used included propargite and fenbutatin-oxide. Most frequently treated crops for fenbutatin oxide included tangerines, nursery crops, and nut crops. For propargite, most use occurred on corn, nut crops, nectarines, and grapes.

The acute systemic toxicity of the ATP-synthase inhibitors is low (Table 5). However, with sufficient contact, propargite and the 2 organotin compounds can cause severe irritation of the eyes and the skin. At the beginning of the California surveillance program, in 1974, surveillance reports documented problems in mixer/loaders arising from use of propargite. These partially resolved by the introduction of a formulation distributed in a water soluble packaging that allowed placement in a mix-tank without puncturing the bag. A large scale field residue episode resulted from the introduction of a new formulation with a markedly higher deposition rate and possibly longer dissipation time than the conventional wettable powder (CDPR, WHS report).

A 1988 dermatitis outbreak among stone-fruit harvesters identified a safe surface (“dislodgable”) residue level for harvesting orchard crops. Surface residues in the orchard blocks harvested by 3 affected crews ranged from 0.55 to 1.91 µg / cm2, In blocks harvested by the unaffected crew, surface residues ranged from 0.14- 0.82 with a median value of 0.2 μg/cm2. These results, along with concerns about possible reproductive effects found in animal studies led to adoption of a 21 day re-entry period on stone fruit, a 30 day re-entry for hand labor tasks in vineyards.

(Based upon dermal exposure studies,[1] some vineyard hand labor tasks have longer re-entry time than tree fruit harvesting because of expected higher peak exposures).

The use of propargite did not decrease immediately after the new re-entry level but led to changes in the order of work: scheduling hand labor tasks before rather than after propargite applications. Propargite use peaked in the 1990’s after the long re-entry interval was established (1,691,679 lbs in 1993), but decreased markedly by 2016 (206, 164 lbs of reported use). By inference, the comparatively low 2016 propargite use rate resulted from the long re-entry interval only after the introduction of multiple alternative active ingredients.

California illness registry data showed 173 cases associated with propargite as the only implicated pesticide between 1992 and 2017. These included 46 cases involving pesticide handlers, and 122 involving field workers exposed to pesticide residue. Dermatitis and eye irritation were frequent in both applicators and field workers. Other field workers and other outdoor workers experienced symptoms during drift episodes. A single priority episode (36-FRE-95), probably related to over-application of propargite, accounting for 65 fieldworker cases.

Fenbutatin oxide

Fenbutatin accounted for 7041.02 lbs (%) of 213,204.0 lbs total for the group MOA., 235 (%) of 2,208 total apps for group, 5593 (%) of total 92814 acres. The California illness registry showed 2 cases associated with fenbutatin-oxide as the only implicated pesticide between 1992 and 2017. These included a case of conjunctivitis and corneal injuries in a mixer loader following an accidental direct exposure (2003-1281), and a field worker with non-specific symptoms (headache and throat irritation) associated with a possible drift exposure (2008-918).

Wildlife toxicity issues

An organotin related to fenbutatin oxide, tibutyltin oxide (TBTO) had extensive use as an algaecide, molluscicide, and fungicide in antifouling paints until 1997. As shown in Table 6 TBTO has significant reproductive toxicity for the toxicity for the test species, Daphnia magna, and a long environmental half-life. It accumulates around harbors and marinas, causing detrimental effects on clams and oysters.

Fenbutatin-oxide has a dissipation time (DT50) of 200-300 days and similar reproductive

toxicity in Daphnia magna, based upon the 21 day test. No invertebrate toxicity data was located for propargite. Both propargite and fenbutatin-oxide have lower water solubility than TBTO and less likelihood of becoming a water pollutant because of their use in agriculture.

Uncouplers of oxidative phosphorylation via disruption of the proton gradient, IRC 13

[1] The relative exposure by crop and work task is summarized by the transfer rate factor in the equation: – µg of exposure/hour of woprk = µg/cm2 of leaf residue x Transfer rate factor (cm2/hr). For example 8 hours of work turning cane in a vineyard with a propargite residue of 0.5 µg/cm2 x (Transfer rate factor 8000-30000 for turning cane) = 0.5 x 8000 (or 30000) = 4000 -15,000 ug of potential dermal exposure. Tree crop transfer rate factor 10,000-20,000 cm2/hr reflects lower expected peak exposure compared to turning cane in a vineyard.

Chlorfenapyr CAS # 122453-73-0 Aramite CAS # 140-57-8

Uncoupling protein – mus musculus 307 Aa –

J. Biol. Chem. 263 (25), 12274-12277 (1988)

PUBMED 3410843

An upstream enhancer regulating brown-fat-specific expression of

the mitochondrial uncoupling protein gene

JOURNAL Mol. Cell. Biol. 14 (1), 59-67 (1994)

PUBMED 8264627

A recent review (Cells, 2019) described current understanding of uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation (abbreviated as “OxPhos”) . OxPhos uncoupling agents include organic molecules that pass through lipid barriers while also binding protons. Examples include nitrophenols, halothane, barbituates, and lipophilic weak acids. These include free fatty acids and more complex ring compounds that can diffuse an electrical charge through an aromatic ring – classical uncouplers such as carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoro-methoxyphenyl hydrazone (FCCP) and carbonylcyanide-3-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP). Other agents passing protons through lipid membranes include nucleotides and proteins acting as a part of normal cellular biochemical mechanisms.

Background

In 1933 Tainter discovered that dinitrophenol (DNP) caused significant weight loss; it proved effective in the majority of users without side effects, but caused cataracts and liver injury in significant minority. By 1938 the FDA labelled DNP unfit for human consumption, but illegal uses continued.

In 1981, a weight loss clinic marketed DNP as “intracellular hyperthemia therapy”, used by thousands of patients before rediscovery of its secondary effects (Grundlingh, et al 2011). Although nitrophenols do pass easily through the skin (ATSDR, 2021), its characteristic toxidrome has occurred most notably after ingestion as a drug or illegal nutritional supplement.

Use data

Along with other phenol compounds (dinocap, pentachlorophenol) DNP had use as a fungicide and insecticide in wood treatment products. The product registered in 1974 (909-59, 63% AI) does not exist in the current California registration data base. Possibly similar products, with a different percentages of active ingredient exists in the US EPA label database identified as “Cooke liquid doo-spray” or “Wonderful 70 insecticide”. Pentachlorophenol also uncouples oxidative phosphorylation (J Biological Chemistry 1954), but falls under the multi-site activity

classification. The effect DDT on oxidative phosphorylation is considered a secondary effect, with its main effect on the sodium channel in the nervous system.

For 1974 records showed 1 application of dinitrophenol and 298 applications of dinocap, a total of 3066.4066 lbs. The 10 dinocap registration numbers found included 5 with a product label retrieved from the US EPA pesticide label site. One product contained only dinocap, the other 4 products contained multiple AIs, including dioxathion, endosulfan, dicofol, and rotenone. Pesticide use records for 1974 also show 4 applications of the oxidative phosphorylation “inhibitor” aramite, used on citrus. Its structure closely resembles propargite, with a terbutyl sulfite ester with a chlorine substituted for the propargyl group. This suggests that its insecticidal properties might result from inhibition of ATP synthase.

Table 5 shows category I acute toxicity for 2,4-dinitrophenol, but category III toxicity for dinocap and aramite. An illness summary report for the years 1972 and 1973 indicated an “X” for the occurrence of acute systemic illness, skin and eye for dinitrophenol. It did not describe the number of cases or give individual illness details (HS 40). No California illness records exist for aramite, but it is listed as probable human carcinogen because of liver and gallbladder cancer in animal studies.

2016 data show, chlorfenapyr, first registered in California in 1995 (241-55128-EX, 241-55126-EX), as the only insecticide acting as an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation. Chlorfenapyr originally derived from research on dioxapyrrolomycin, a fermentation product of Streptomyces fumanus, modified in order to reduce its mammalian toxicity (Kuhn and Armes, 2019). It does not cause significant eye or skin irritation, but data are not available for respiratory irritation or skin sensitization (Table 5).

Data totals showed 4,059.58 lbs sold (0.002% of total), 23,667.2 lbs reported use (0.02% of total), 930 agricultural applications (0.07% of total). Review of 14,430 invidual application records showed 92% used for structural pest control. Kuhn and Ames (2019) report that chlorfenapyr has no repellent properties to provoke structural pests to avoid contact and provides good initial control of termites. It leaves a residue that provides long lasting control. A single termiticide-insecticide product (241-55141-EY, 21.4% AI) accounted for 68.5% of applications and 98.9% of total lbs reported used. yr

Illness data

California registry data show 23 total cases, including 17 mixed exposures to other AIs (pyrethroids, pyripoxyfen, fipronil, hydroprene, and indoxacarb). In the 6 cases with isolated exposure to chlorfenapyr, 1 patient (2010-1106) complained of skin irritation after reporting a director exposure from a structural treatment. In 2 possible pediatric ingestions (2017- 855 2012- 1060) symptoms included vomiting, nausea and dizziness. In 3 cases with possible airborne exposure (2006-58, 2010-215, 2011-56) symptoms included shortness of breath, dizziness and muscle cramps.

Compounds interfering with insect behavior, growth, and development

Compounds affecting insect development target synthesis of lipid and chitin, and mimic the behavior of several insect hormones. The biological targets include insect pheromones controlling reproduction, ecdysone, juvenile hormone, and chitin . Modifiers of insect behavior –Individual pheromone AI’s and non-specific odorants used in pheromo

Leave a comment